Are all AI-generated works void of authorship and originality?

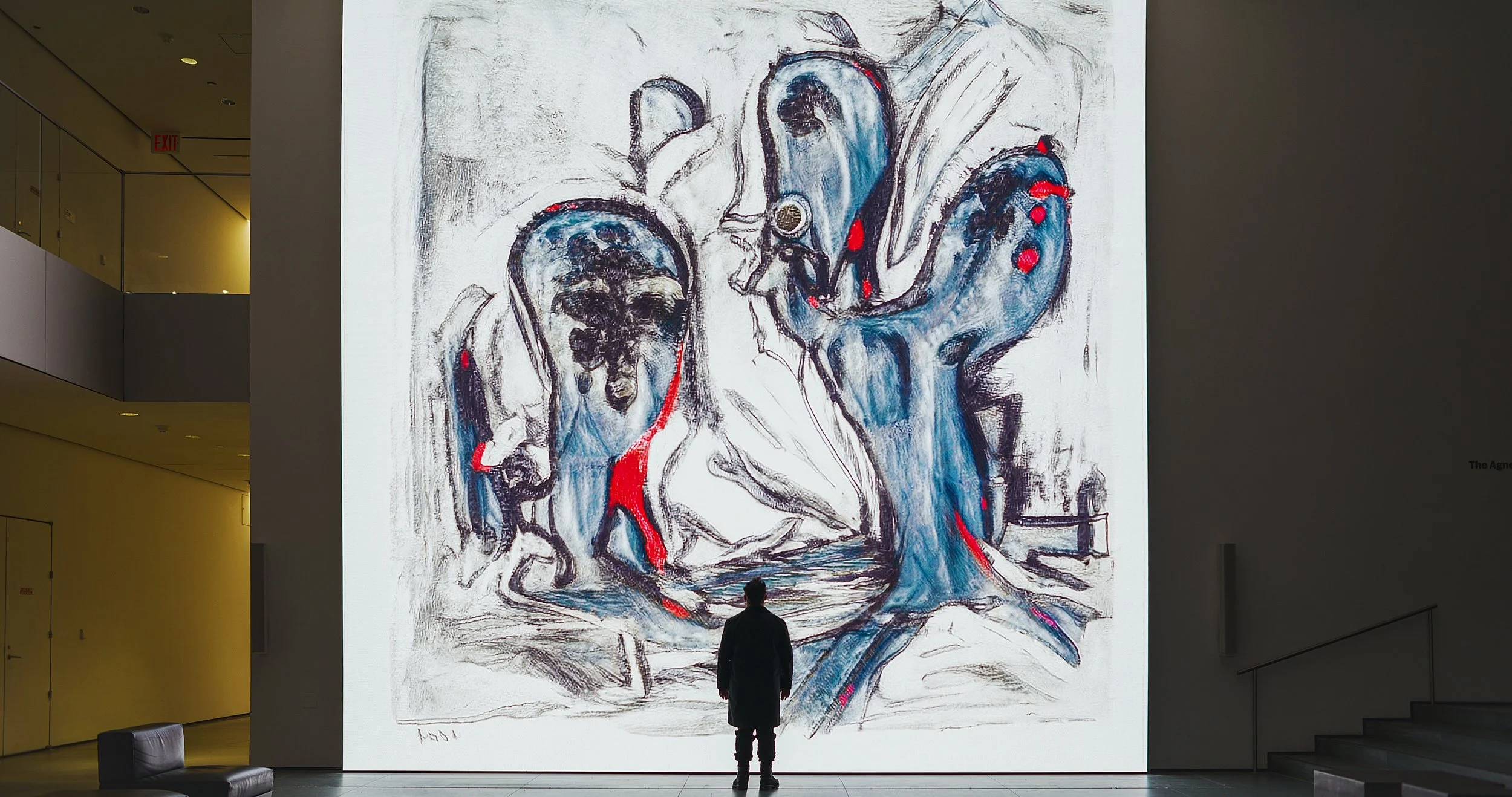

Installation of Unsupervised at MoMA. Photo courtesy of Refik Anadol.

Background

On March 16, 2023 the U.S. Copyright Office (“Office”) issued a statement of policy for works containing material generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI). [1]. According to the policy, when the “work’s traditional elements of authorship were produced by a machine, the work lacks human authorship” and cannot be protected by copyright. [2].

The Office proffered an example where an AI-generated visual work would not receive copyright protection: a user provides the AI “solely a prompt” and the AI produces the work in response to the prompt. [3]. In this example, the visual work would not qualify for copyright protection because a human did not create the “traditional elements of authorship”. [4]. According to the Office, the AI, not the user, has the creative control because the AI determined the expressive elements of the output based on the prompt. [5].

The Office, however, clarified that there are cases where a work containing AI-generated content can still receive copyright protection. [6]. The Office cited the copyright registration for the graphic novel Zarya of the Dawn. [7]. The images in Zarya were created by the AI service Midjourney, while the text was authored by a human being, Kristina Kashtanova. [8]. The Office determined that the selection, coordination, and arrangement of Zarya’s written and visual elements were protected by copyright law but the AI-generated images were not. [9].

Although good news for authors of Zarya-type works, there is a more fundamental issue with the Office’s current policy. According to the Office, “users do not exercise ultimate creative control over how such systems interpret prompts and generate material.”

But, if the user did have ultimate creative control over the AI, would the Copyright Office’s policy hold up?

Installation of Unsupervised at MoMA. Photo courtesy of Refik Anadol.

The Work

To add some color to the hypothetical, let us evaluate Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised, currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MoMA). [10]. To create Unsupervised, Anadol trained a machine-learning model using MoMA’s entire digitized art collection (138,151 pieces of metadata) and the actual environment (light, movement, acoustics) of MoMA’s lobby. [11], [12], [13]. The processing of all the data resulted in Unsupervised, a moving and evolving piece of visual and acoustical media. On a galactical level, Unsupervised is what a machine would dream about after viewing over 200 years of art featured in MoMA. [14]. It is a fantastical “hallucination” of what art was and what it could be.

On molecular level, Unsupervised was created using machine learning model Style Generative Adversarial Network (StyleGAN). [15]. Anadol selected a specific model, StyleGAN2 with adaptive discriminator augmentation, and trained the model with certain subsets of MoMA's collection to create embeddings in 1024 dimensions. [16]. The sorted subsets were then organized into thematic categories, like artistic movements. [17]. The model then created the “hallucinations” of these categories in a multi-dimensional space. [18].

The question remains whether Anadol’s Unsupervised would be entitled to copyright protection under the Office’s new policy. And if it does not, should the policy be revised to allow purely AI-generated materials to receive copyright protection based on the level of creative control a user has over the AI?

There are three basic requirements for copyright protection of a work: it must be a work of authorship, it must be original, and it must be fixed in a tangible medium of expression. [19]. The fixation requirement of Unsupervised is not in question, but what it is whether Unsupervised is original and whether it is a work of authorship.

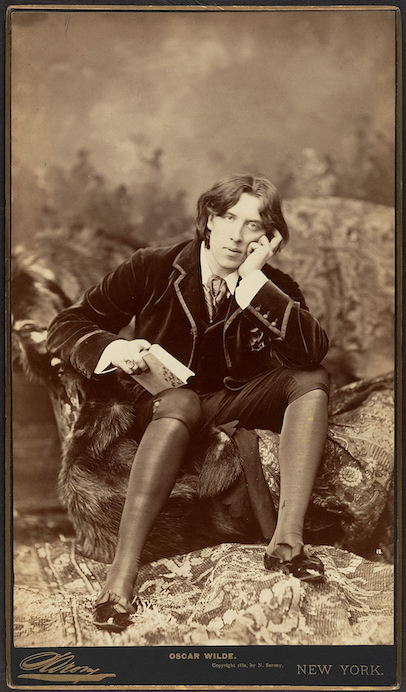

Oscar Wilde No. 18 by Napoleon Sarony (1882), the photograph at issue in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony. Provided by Wikipedia Commons.

Originality - Mechanical Reproduction

Turning back the clock to 1884, the Supreme Court in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony took up the issue of whether a photograph was an original work of art. [20]. The plaintiff had taken a photograph of Oscar Wilde, titled “Oscar Wilde, No. 18”, and sued the defendant for copyright infringement. [21].

The defendant argued that photographs were not productions of an “author” because photographs are merely “a reproduction on paper of the exact features of some natural object or of some person” and contained “no authorship”. [22]. The Court, while acknowledging that photographs are, by definition, a mechanical reproduction, held that so long as the photograph at issue is “representative[] of original intellectual conceptions of the author,” it could be protected by copyright. [23].

The Court determined that the plaintiff posed the subject, Oscar Wilde, arranged the set and background, and adjusted the lighting and shade in order to evoke “the desired expression” from Oscar Wilde. [24]. The result, the Court held, was a work of art entitled to copyright protection. [25].

The Office cited Burrow in its policy statement, reiterating the holding that “mechanical reproductions” are not entitled to copyright protection. [26]. However, the Office acknowledged that works made using mechanical processes that are “original mental conception[s]” of the author can be copyrightable. [27].

Anadol’s creation of Unsupervised is akin to the creation of Oscar Wilde’s portrait in Burrow. Anadol created the set and the background by selecting a specific input for his AI model, 200 years of artwork featured in MoMA. He then adjusted the lighting and the shade by feeding environmental data of the MoMA lobby into the AI model.

Like the photographer in Burrow, who conceived of a particular expression of his subject Oscar Wilde, Anadol conceived of a machine’s dream after digesting over 200 years of artwork. His AI model, like a camera, was simply a mechanical process or tool he used to execute this original conception.

"Map making, circa 1943" by Archives Branch, USMC History Division is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Authorship - Under the Authority of the Author

If it can be established that Unsupervised is an original work of art, then the next question is whether Anadol is the author of that work of art.

The Copyright Act defines a work to be “fixed” when an author or “under the authority of the author” a work is either embodied in a copy or in a manner that can be perceived for more than a transitory period. [28]. That is, an author is either one who actually creates an embodied expression, or, authorizes another to perform the embodiment on their behalf. [29]. An authorization, though, “must be rote or mechanical transcription”. [30]. For example, a photographer who pays for prints of her digital photographs is the author of those photographs, and not the employee of the printing company who actually printed the photographs, even though the employee actually produced the prints. [31].

In Andrien v. So. Ocean Cty. Chamber of Commerce, the Third Circuit examined the issue of authorization. [32]. In that case, the plaintiff had instructed a printing firm to print map composites. [33]. The plaintiff collected maps used by taxis, obtained a map for locating shipwrecks, and compiled a list of landmarks, fishing sites, and street names. [34]. He then calculated the scale of the map by driving between intersecting streets and measuring the distance on his car’s odometer. [35]. The plaintiff then brought his materials to the printing press looking for help to create the final map composites. [36]. The maps that the plaintiff collected had different scales and illegible street names. [37]. Thus, the printing press assigned an employee to help re-letter and re-label the street names, add map designations for points of interest, and synchronize the scales. [38].

The Third Circuit concluded that none of the employee’s activities “intellectually modified or technically enhanced the concept articulated by” the plaintiff. [39]. The employee, acting on the plaintiff’s order, simply arranged the plaintiff’s work in a more legible form so it could be printed into maps. [40].

At least in the eyes of the Third Circuit, the question whether Anadol is the author of Unsupervised would depend on whether Anadol exercised sufficient supervision and control to prevent the AI from “intellectually modif[ing] or technically enhanc[ing]” the concept Anadol created.

In other words, was the AI… unsupervised?

Installation of Unspervised at MoMA. Photo courtesy of Refik Anadol.

Anadol conceived that Unsupervised to be what a machine would dream of after viewing 200 years of art exhibited at MoMA. Thus, the concept of the work itself was created by Anadol. Anadol then trained the AI by providing certain data: the thousands of exhibits that have graced MoMA and the physical environment of MoMA’s lobby. The AI did not select or contribute to the data.

Thus, like the plaintiff in Andrien, Anadol provided the overall concept and the materials necessary to make the final product. And like the plaintiff in Andrien, Anadol just needed help creating the final product. Help, not creative input.

Considering the above, it remains to be seen whether the Office’s position that “users do not exercise ultimate creative control over how such systems interpret prompts and generate material” can hold. As demonstrated by Anadol, there are at least some artists creating AI-generated works who exert creative control in: the AI models selected, the data used to train the models, and therefore, the creative output that such models produce.

Further, the case of Unsupervised shows that at least some works of art generated entirely by AI can meet the statutory requirements for copyright protection. Hence, a bright-line rule that AI-generated works are not entitled to copyright protection is not consistent with established Copyright case law. At minimum, works created using AI suggest a case-by-case basis review, taking into consideration whether the user conceives of an original work and has suficient control over the AI process.

An earlier version of this article was originally published on Moraru & Nacht LLC’s website on July 3, 2023.

Sources

[1] U.S. Copyright Office. “Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence.” A Rule by the Copyright Office, Library of Congress on 03/16/2023, March 16, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/16/2023-05321/copyright-registration-guidance-works-containing-material-generated-by-artificial-intelligence#citation-10-p16191.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Kasunic. “Re: Zarya of the Dawn (Registration # VAu001480196)” U.S. Copyright Office, February 21, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.copyright.gov/docs/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf.

[10] “Refik Anadol Unsupervised.” MoMA. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5535.

[11] Id.

[12] “Unsupervised-Machine Hallucinations-MoMA” Refik Anadol. https://refikanadol.com/works/unsupervised/.

[13] Anadol et al. “Modern Dream: How Refik Anadol Is Using Machine Learning and NFTs to Interpret MoMA’s Collection” MoMA, November 15, 2021. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/658

[14] Refik, supra note 12.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] 17 U.S.C. 102(a).

[20] Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 56 (1884).

[21] Id. at 54.

[22] Id. at 56.

[23] Id. at 58-9.

[24] Id. at 60.

[25] Id.

[26] U.S. Copyright Office, supra note 1.

[27] Id.

[28] 17 U.S.C. § 101.

[29] Andrien v. So. Ocean Cty. Chamber of Commerce, 927 F.2d 132, 134-5 (3d Cir. 1991).

[30] Id. at 135.

[31] See Id. at 135.

[32] Id. at 134.

[33] Id. at 133.

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id. at 135.

[40] Id.